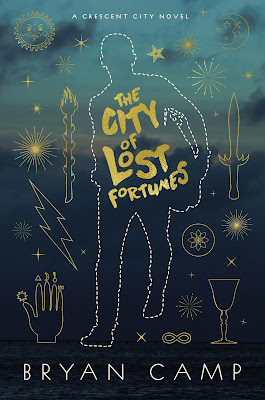

SPOTLIGHT: The City of Lost Fortunes by Bryan Camp @bryancamp @HMHCo

The City of Lost Fortunes

by Bryan Camp

🎆 HAPPY PUBLICATION DAY! 🎆

Really digging on this cover!! Check out today's spotlight - The City of Lost Fortunes by Bryan Camp! Keep reading to get a blurb, learn about the author and a Q&A!

The fate of New Orleans rests in the hands of a wayward grifter in this novel of

gods, games, and monsters.

It’s 2011, six years after Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans. The city is still desperately trying to

survive its rebuilding, to ensure it has a place in the future. It’s also a world full of magic, monsters, and

miracles. Street magician Jude Dubuisson is burdened by his past and by the consequences of the storm,

because he has a secret: the magical ability to find lost things, a gift passed down to him by the father he

has never known—a father who just happens to be a god. When the debt Jude owes to a fortune deity

gets called in, he finds himself sitting in on a poker game with the gods of New Orleans, who are playing

for the heart and soul of the city itself.

In Bryan Camp’s debut novel, THE CITY OF LOST FORTUNES (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt/A John Joseph

Adams Book, April 2018), the God of Fortune meets a Voodoo king and an angel meets a vampire in a

mythology mashup that fits its diverse New Orleans setting, and represents a fantasy-literary-mystery

fiction crossover that will be interesting to lovers of intellectually complex literary novels while still

containing the action and intricate plot beloved by fantasy and mystery fiction fans.

Through the lens of New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, the book evokes issues of class struggle, race

relations, and cultural preservation, which makes it highly appealing and relevant as commentary

beyond fiction to today’s current affairs. Historically, New Orleans has accumulated a wide variety of

cultures and faiths in its demographic. THE CITY OF LOST FORTUNES explores the conflicts and

prejudices that hinder our collective growth, while celebrating the unique strengths and traditions of

our varied heritages. This novel will surely interest a readership as diverse as its cast of characters.

BRYAN CAMP is a graduate of the Clarion West Writer’s Workshop and the University of New Orleans’

Low-Residency MFA program. He started his first novel, The City of Lost Fortunes, in the backseat of his

parents’ car as they evacuated for Hurricane Katrina. He has been, at various points in his life: a security

guard at a stockcar race track, a printer in a flag factory, an office worker in an oil refinery, and a high

school English teacher. He can be found on twitter @bryancamp and at bryancamp.com. He lives in New

Orleans with his wife and their three cats, one of whom is named after a superhero.

PRAISE FOR THE CITY OF LOST FORTUNES

“A phantasmagoric murder mystery that wails, chants, laments, and changes

shape as audaciously as the mythical beings populating its narrative… the

engaging style, facility with folklore, and, above all, impassioned love for the city

its characters call home keeps you enraptured by the book's most chilling and

outrageous plot twists. One hopes for more of Camp's dangerous visions to spring

from a city that, as he writes, ‘is a great place to find yourself, and a terrible place

to get lost.’” —Kirkus

“There isn’t a dull page as Jude determines who his real friends are. Anne Rice

fans will enjoy this fresh view of supernatural life in New Orleans, while fans of

Kim Harrison’s urban fantasy will have a new author to watch.”—Booklist

“A masterly game played by gods and monsters, a devastated city trying to

rebuild, and compelling characters struggling to find their place in a strange world

are all pieces of this fantastic and enthralling puzzle of a story. VERDICT Camp's

thoroughly engaging debut is reminiscent of Neil Gaiman's American Gods, with

the added spirit of the vibrant Big Easy.” (Debut of the Month)—Library Journal

“Camp’s fantasy reads like jazz, with multiple chaotic-seeming threads of deities,

mortals, and destiny playing in harmony. This game of souls and fate is full of

snarky dialogue, taut suspense, and characters whose glitter hides sharp fangs. […]

Any reader who likes fantasy with a dash of the bizarre will enjoy this trip to the

Crescent City.”—Publishers Weekly

Take a walk down wild card shark streets into a world of gods, lost souls, murder,

and deep, dark magic. You might not come back from The City of Lost Fortunes,

but you’ll enjoy the trip.

—Richard Kadrey, bestselling author of the Sandman Slim series.

In The City of Lost Fortunes, Bryan Camp delivers a high-octane tale of myth and

magic, serving up the best of Neil Gaiman and Richard Kadrey. Here is New

Orleans in all its gritty, grudging glory, the haunt of sinners and saints, gods and

mischief-makers. Once you pay a visit, you won’t want to leave!

—Helen Marshall, World Fantasy Award-winning author of Gifts for the One

Who Comes After.

A CONVERSATION WITH BRYAN CAMP

You started writing this book in the car as you and your parents evacuated in advance of Hurricane

Katrina. What was it about that experience that inspired the themes of the novel?

I’d have to say that the most influential part of the experience for me was the simple fact that I was able

to evacuate. Many people lack the means or the resources or the ability to just leave. I was fortunate

enough be able to rely on family to get out of harm’s way. In fact, a ridiculous amount of luck went into

my experience of the storm. At the time, I was working my way towards an undergrad degree, waiting

tables at a steakhouse, and sharing a house with a couple of friends. Earlier that week, I’d decided to

move back in with my folks to cut down on rent. Which means that when Katrina made its sudden surge

from a no-big-deal storm into a monster, all my stuff was already packed up. If I tried to sell that

narrative to a reader it would stink of authorial intrusion and deus ex machina, but real life doesn’t have

to feel earned or fair like fiction does. The question for me was, was I destined to slip away from the

storm unscathed or was it just dumb luck? What’s really the difference between those two things? So a

lot of the focus on luck and fortunes and destiny and privilege that’s in the book comes from me trying

to grapple with that.

Another thing that occurs to me is that the technological feedback of 2005 wasn’t as immediate as

today. There was no marking yourself safe on Facebook. No cell phone videos going viral on Instagram

and twitter. So for a period of about a week, until my father and I left my mom and two siblings behind

in Florida and drove back, we had only the national news coverage and Yahoo message boards to tell us

about the condition of our home. If the news didn’t show your house, you had only the internet to turn

to, and those message boards were rife with gossip, inaccuracies, and outright lies. That restaurant

where I worked? According to the message boards, it burned down when the gas station next door

caught fire. Based on the flooding they related, our home almost certainly took water. Tornadoes and

looting—don’t get me started about how we define looting—and everything but zombies were being

reported. As it turned out, my immediate family was as fortunate in the aftermath as we were in being

able to escape. But for a week, as far as I’d known, I’d lost pretty much everything. Home, job, most of

my worldly possessions, my ability to get back and forth to school, all of it. I roll my eyes whenever a

disaster’s impact is measured in terms of a dollar amount of damage because when we think about loss

just in terms of stuff, we miss the point. Make no mistake, the cost and labor and emotional toll of

actually having everything you own torn away from you is devastating. My wife, friends, and members

of my extended family weren’t nearly so lucky, and I don’t want to minimize the challenges they faced in

recovering from that material loss. But what can’t be measured is that other kind of loss, the loss of

community and identity and, frankly, humanity that can be stolen just as easily as material possessions

can be destroyed. So I tried to talk about that in the book too, and I hope I did it justice.

Why did you decide to set the book in 2011—six years after Katrina—rather than make it fully

contemporary?

The simple answer is that it took me just over a decade to write this book. The very first scene—which

made it into the final draft largely unchanged—was written as a writing exercise in Bev Marshall’s

undergrad creative writing class in, obviously, 2005. I finished that very first draft in 2008 or so, then

rewrote it as my MFA thesis—with Amanda Boyden, Joseph Boyden, and Jim Grimsley as my

committee—in 2010. I rewrote it again after I attended Clarion West in 2012 finishing around 2014 or

so, and after my now agent Seth Fishman first saw it in 2015, I did a pretty substantial revision, though

not quite a rewrite, which took me through 2016.

Though the core of the book has remained the same throughout, the setting in terms of time was one of

the things that kept shifting around. At first, it was set vaguely pre-Katrina, with the storm this

prophesied, malevolent threat looming on the horizon. I wince when I think about how exploitive that

premise sounds to me now, but it very quickly became obvious to me that the storm was too important,

too impactful to treat as a Macguffin. Which is why what started out as a pretty standard noir detective

story—with mythology thrown in because I’m a nerd—turned into a thing that took me years to get

even a draft that I was happy with. That version was set about three years after the storm and was all

about the aftermath and immediate recovery.

As years and edits went on, though, it became clear to me that narratives about the immediate

aftermath and recovery were already being written and done by more qualified writers. It was also

harder and harder to hold on to the memories of those first years right after the storm, both in terms of

specific details and the collective emotion. Because of this, when I started the last rewrite I decided to

move it to 2011. That time period felt like a good balance between “still dealing with the impacts of the

storm” and “ready to move forward to something new.”

When I was doing the final edits with John Joseph Adams, he brought up the setting and asked why we

didn’t just make it contemporaneous, as it would fix some of the issues of rewrite palimpsests we kept

finding, like character using a PDA or not just using google to find something out. Ultimately, though,

New Orleans is a much different city today than it was in 2011. Once we hit that ten year anniversary,

we seemed to finally manage to attain a post-post-Katrina mindset, if that makes sense. So I guess the

real simple answer for “why 2011?” is that 2008 was too close to the storm and 2016 is too far away for

the story I wanted to tell, but it took me ten years or so of writing to figure that out.

Talk about syncretic mythology and how that applies to the book.

Syncretism is the term for when religious or cultural traditions come into contact and merge rather than

one entirely destroying or isolating the other. Sometimes it’s one culture incorporating traditions from

another overtly, like the adoption of certain pagan rituals and symbols into Christian holidays, which is

where we get Christmas trees and Easter bunnies. Other times it’s more subversive, like Africans who were enslaved and sold in New Orleans finding analogues of their own pantheon among the Catholic

saints, so that they could continue their own worship practices despite being forced to convert to

Christianity. This is incredibly simplified, of course, but I can only talk about this topic briefly or at great,

exhaustive, oh-god-is-he-still-talking-about-myths length.

At any rate, between this idea and Jung’s concept of archetypes it seemed strange to me that just about

everything I came across in fiction felt woefully myopic. Why were all the books about vampires direct

descendants of Dracula and European folklore? Why were the angels always Christian? Now obviously,

part of the problem here was that I simply hadn’t read widely enough to find these books I was just

assuming didn’t exist. I hadn’t even read American Gods yet. So like many young writers, I confused my

own ignorance with brilliance and starting building a world in my head. A world where the gods of myth

could assimilate the way a cultural practice could. One where Legba and Thoth and an angel and a

vampire and a fortune god could sit down at a poker table together and play a game with mortal lives.

I’m glad I didn’t know way back then that there were books like mine already in the world, because

otherwise I might never have started this one.

Talk about how the history and culture of New Orleans inspired the book.

Well, it’s a book about myths walking the streets of the real world, so New Orleans is perfect because

the city itself is kind of a myth. Or more accurately, since its founding it’s been a few different myths.

The city was originally founded as a French colony in order to seize control of the Mississippi, except

that’s not entirely true, because the geographically foolhardy choice of location had a lot more to do

with Bienville’s personal motivations than strategy. It was also a utopia in a new world where French

citizens could flourish, if you believed the propaganda put out by John Law, who wanted to use the

colony to rebuild the French economy through some super-shady real estate speculation. In reality it

was a swamp filled with yellow fever, hurricanes, and convicts.

The city’s identity is all tied up in its French heritage, but it was a Spanish colony almost as long as it was

French. France eventually bought it back, just to flip it and sell it to the U.S. in the Louisiana Purchase.

And speaking of myths, the French Quarter isn’t even French! Around 80 percent of it burned down in

the late 1700s, when the city was owned by Spain, so it got rebuilt using Spanish architecture.

It’s also a port city, with the mélange of cultures and exchange that implies, along with being a major

hub of the slave trade. So you’ve got the myth of the ‘melting pot’ in terms of beneficial cultural

assimilation, and the myth of slavery being somehow different in the city, because we were so

cosmopolitan and had such a large population of free people of color. In truth, we’ve never had a sincle

culture so much as we’ve had a handful of cultures trying to coexist and appropriating and assimilating

and benefiting and destroying one another. For every image of different ethnicities celebrating together

on Mardi Gras day, there’s the reality of neighborhoods and schools that remain effectively—if not

explicitly—segregated. For every historical account of how good free people of color had it in antebellum New Orleans, there’s the reality of an economy and a history built around owning human

beings and profiting from their labor.

Then there’s the myth of modern New Orleans: drunken debauchery on Bourbon Street and Carnival.

Spoiler: those aren’t locals. Bless every one their rum-soaked hearts too, because the city depends on

tourism for survival.

I hadn’t really considered it before this question, but the history of New Orleans fits the idea of the gods

I discussed earlier, that idea that they can jump from one pantheon to another, or shed their skin and

become something else. New Orleans’ identity has always been a shifting thing, a fiction. When it

happens once, it’s a lie. When it happens for a couple hundred years, it’s a myth.

What works or authors were the primary influences on this book?

In that same semester of undergrad where I wrote the first scene of this book in a creative writing class,

I also took a literature course focused on detective fiction. It was there that I was introduced to James

Lee Burke and Walter Mosley and Raymond Chandler and Dashiel Hammett, so if one half of this book’s

chromosomes came from the parent of the mythology I’d been reading since junior high, the other half

of its DNA came from those noir mysteries. A lot of that syncretic myth I discussed earlier really came

alive for me in the pages of Lewis Hyde’s Trickster Makes This World, which I discovered in the

bibliography after I was finally introduced to Neil Gaiman’s American Gods. Interestingly enough,

though, American Gods was more influential on this book in its absence, by which I mean I was only able

to start it because I hadn’t yet read it, and I was only able to keep writing it by distancing myself from

the large, looming shadow of Gaiman’s work. For example, his gods are entities generated and sustained

by human worship, so I went the other way and wrote about gods who don’t really give a damn if we

know they’re there or not. There were also a number of books I discovered along the way that did some

of what I was trying to do in terms of tumbling all the myths together: Charles de Lint’s Newford books,

the early books in Laurell K. Hamilton’s Anita Blake series, and Esther M. Friesner’s Gnome Man’s Land,

which is a book I sometimes think I made up because I can never find anyone else who’s read it.

And then, of course, there are the writers that get under your skin and—while you can’t point to the

influence they’ve had on a specific piece of writing—instead impact everything you’ll ever write because

they’re the writers you want to be when you grow up: John Crowley. I’ve already said Walter Mosley but

he bears repeating. Ursula K. Le Guin. Jorge Luis Borges. Catherynne M. Valente. Umberto Eco. Zora

Neale Hurston. Stephen King.

HMH will be publishing a second book from you as well. What can you tell us about that?

The next book—which has a working title but I won’t say it because something else that changed

drastically draft to draft with my first book was the title—is set in the same version of New Orleans as

The City of Lost Fortunes, but is about a year and a half after the end of the first novel, and is focused on

a different main character. This book tells the story of a young woman who is also a psychopomp, one of the guides who lead the newly dead into the afterlife. It’s an okay gig, until she shows up at the

appointed time and place to collect the soul of a kid who isn’t there, dead or alive. She looks for him, of

course, but her search keeps getting interrupted by little things like the Gates of the Underworld getting

locked, or destruction gods dropping in unannounced, or a Halloween haunted house full of actual

zombies. She knows this boy is the key to all of the chaos, but what she doesn’t know is whether he’s

running from her, or from something even worse than death.

No comments

Leave a Comment